y 8:45 AM on Monday, February 3, 2026, the streets of Onitsha Main Market were alive again. Traders pushed carts loaded with goods, customers haggled over prices, and the familiar cacophony of commerce filled the air—a stark departure from the eerie silence that had gripped the market for years.

For Chidi Okafor, a textile merchant who has operated along Lagos Line for fifteen years, Monday’s reopening represented more than just a return to business. “We have been living in fear for too long,” he said, arranging colorful fabrics on his display. “Today, we chose our livelihoods over intimidation.”

The reopening came after Governor Chukwuma Soludo imposed a one-week shutdown of the market on January 27, following traders’ continued observance of the Monday sit-at-home order initially called by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) in solidarity with their detained leader, Nnamdi Kanu. The order, which has disrupted economic activity across Nigeria’s South-East region for nearly four years, had kept markets, schools, and workplaces deserted every Monday.

Soludo’s decision to shut down the market—and his threat of further closures or even demolition of non-compliant shops—forced a difficult reckoning for traders caught between competing pressures: the fear of violence from non-state actors enforcing the sit-at-home, and the economic devastation of losing their businesses.

The gamble appears to have paid off. By mid-morning Monday, over 70 percent of shops had reopened across major trading corridors including Fashion Line, Children’s Wear Line, Accessories Line, and Emeka Offor Plaza. Customers streamed in, relieved to find their favorite vendors back in business.

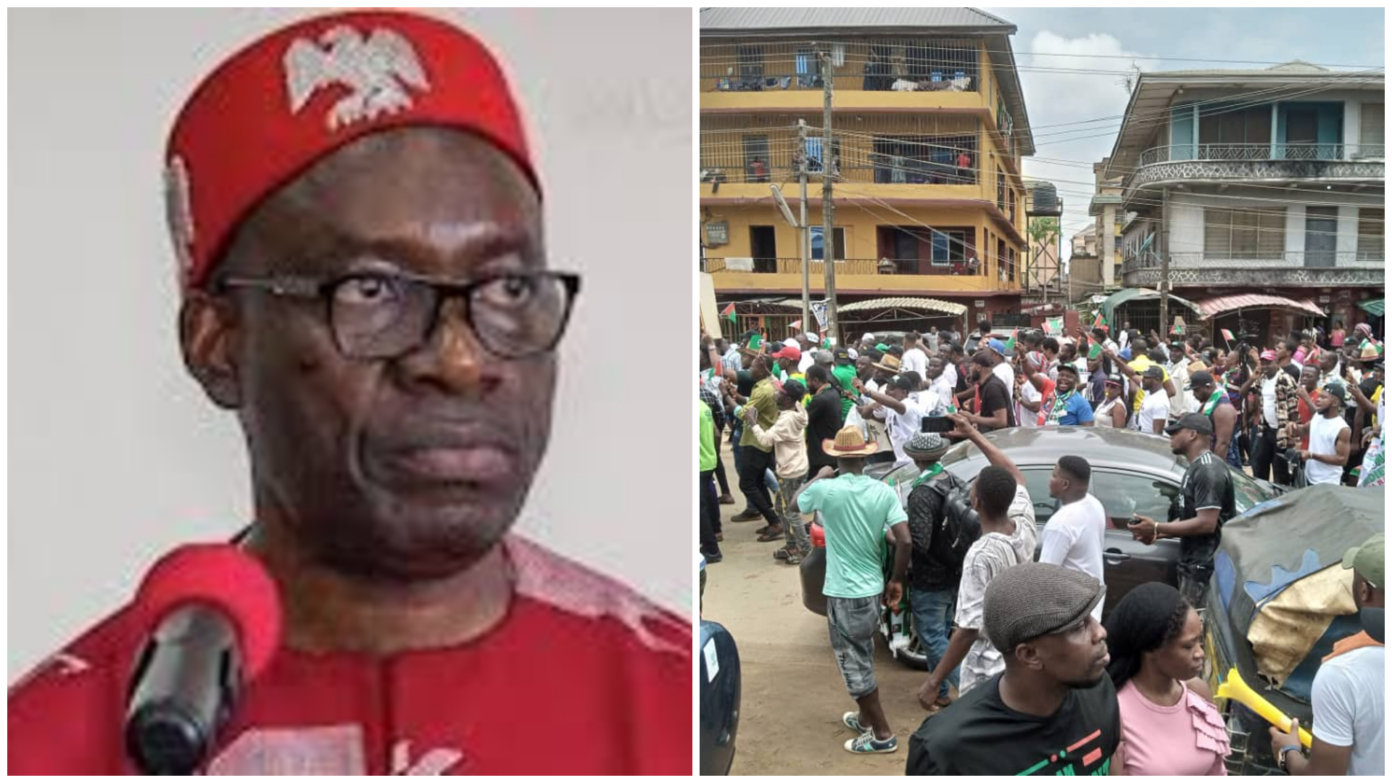

“I am satisfied with the large turnout,” Governor Soludo remarked during a solidarity visit to the market, walking through Oseokwodu market to the Main Market and finally to Emeka Offor Plaza. His physical presence—alongside heavy security deployment—sent a clear message: the government would protect those who chose to work.

A Battle Between Law and Lawlessness

The Onitsha market saga highlights a fundamental tension in Nigeria’s South-East: the struggle between constitutional rights and criminal intimidation masquerading as political protest.

Legal experts note that while citizens have the constitutional right to peaceful protest, the Monday sit-at-home has evolved into something far more sinister. What began as a voluntary show of solidarity has morphed into a regime of fear, with enforcers—many allegedly not even from Anambra State—using violence and threats to compel compliance.

“The current enforcement of the sit-at-home order has transitioned from a political protest to a criminal enterprise,” Soludo declared. IPOB itself, through its lawyer Ifeanyi Ejiofor, has repeatedly disowned the continued sit-at-home orders, calling recent directives “fake” and urging the public to ignore them.

Yet fear persisted. In the past, traders who attempted to open on Mondays faced violence, property destruction, and in some cases, loss of life. One protester captured this paradox in a viral video: “If the security presence used to enforce the market closure could be deployed to protect traders, I will have no problem opening my shop.”

The Economic Cost of Fear

The financial toll has been staggering. Chinedu Nwonu, Chairman of the Onitsha Chamber of Commerce, revealed that the market recorded losses exceeding ₦200 billion during just the six-day closure period. Multiply that across four years of Monday closures, and the economic hemorrhaging becomes almost incomprehensible.

For individual traders, each Monday represented a day of lost income, spoiled perishables, and mounting debts. “We are not politicians,” said Ada Nnenna, who sells foodstuffs at Ose Market. “We are ordinary people trying to feed our families. How can we survive when we lose one day every week?”

The ripple effects extended far beyond Onitsha. Transport workers lost fares, manufacturers lost distribution days, and the entire regional economy contracted. The South-East, already economically disadvantaged compared to other Nigerian regions, could ill afford such self-inflicted wounds.

A Fragile Victory

Monday’s reopening was hailed by market leaders and the state government as a turning point. Chief Humphrey Anuna, President-General of Anambra State Markets Amalgamated Traders Association (ASMATA), commended traders for “putting the issue of Monday sit-at-home behind them.”

However, the victory remains fragile. Adjoining markets like Ochanja and Relief Market recorded significantly lower turnouts, suggesting that fear still grips some sections of the trading community. Governor Soludo’s threat to demolish over 10,000 non-compliant shops within 14 days—though later suspended as normalcy returned—revealed the government’s willingness to use force to break the cycle.

The market chairman, Chijioke Okpalugo, dismissed rumors that he had resigned under pressure from non-state actors, but pleaded with the government to reconsider the planned demolitions. “Normalcy has returned,” he said. “Let us build on this progress rather than punish people who are now complying.”

Looking Forward

The reopening of Onitsha Main Market represents a test case for the entire South-East region. If traders can sustain Monday operations without violence, other markets and cities may follow suit, gradually eroding the sit-at-home’s stranglehold on the region.

Governor Soludo has offered traders a choice: modernize the existing market or allow government to demolish and rebuild it into a world-class trading facility. Either way, he insists, the days of capitulating to illegal orders are over.

For now, the merchants of Onitsha have made their choice. Armed with courage and supported by government security, they have chosen commerce over coercion, livelihoods over fear. Whether this fragile peace holds will depend on sustained security presence, the ultimate resolution of Nnamdi Kanu’s case, and the collective will of traders to reclaim their economic destiny.

As the sun set on Monday evening, Chidi Okafor locked his shop with a sense of cautious optimism. “Next Monday, I will open again,” he said. “And the Monday after that. We have been silent for too long. It is time to work.”