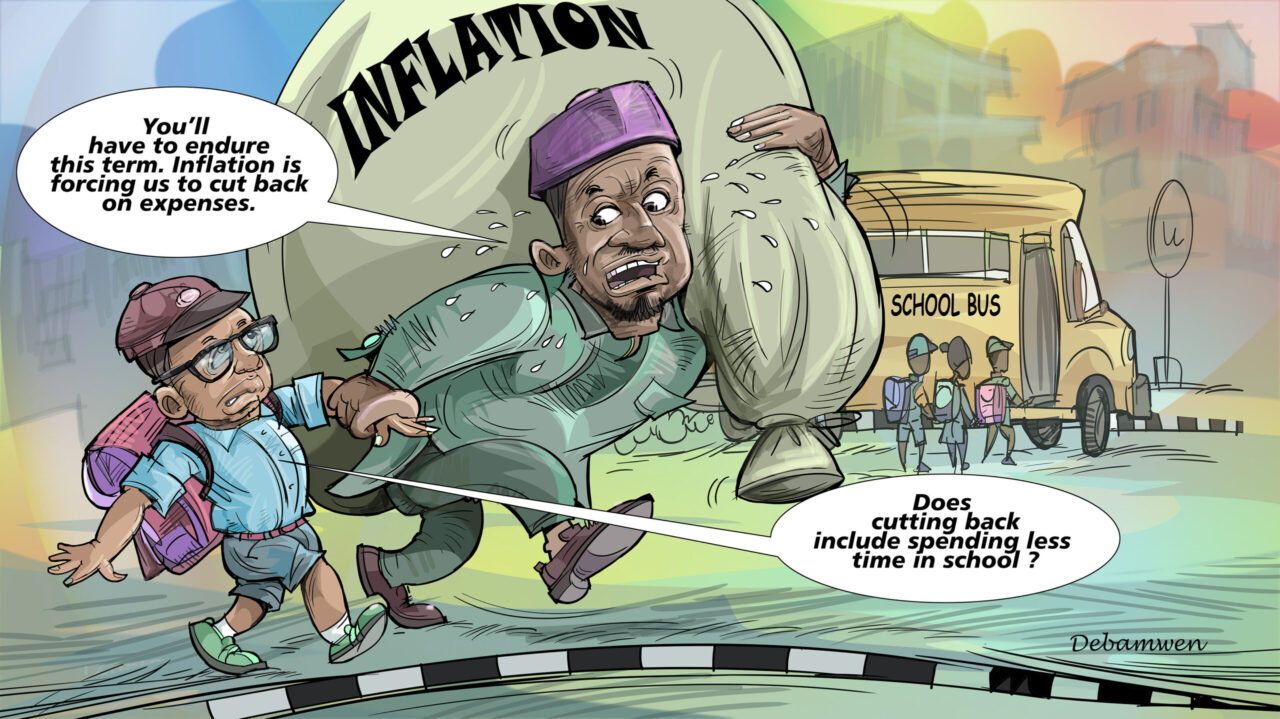

As the summer holidays begin and schools prepare to resume by early September, the joy of the break is already clouded by a harsh reality for many families: the rising cost of sending children back to school.

For many Nigerian parents, especially those in the middle-income bracket, the 2025/2026 school year is arriving with price tags they simply can’t ignore.

“Last year, my daughter’s school fees were ₦180,000 per term. Now they’re asking for ₦250,000,” says Mrs. Kelechi Anozie, a civil servant and mother of three in Lagos.

“And that doesn’t include books, uniforms, or transport. Everything has gone up.”

Schooling Costs in Crisis

Across major cities like Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt, and Ibadan, parents are reporting sharp increases in school fees — some as high as 30 to 50%. But tuition is just one part of the equation. Essentials like textbooks, school bags, stationery, and even meal plans have seen dramatic hikes.

A survey of ten private schools in Lagos and Ogun States by The Nation’s Lens revealed the following:

- School uniforms now cost between ₦25,000–₦40,000 per set, up from ₦15,000 last year.

- Books for primary school pupils average ₦45,000–₦60,000 per term.

- Lunch fees have risen by at least 25%, with some schools charging up to ₦35,000 per child monthly.

- School bus services are now between ₦50,000–₦100,000 per month, depending on the route.

“We are not increasing fees because we want to,” explains Mr. Dayo Ogunlana, proprietor of a mid-tier private school in Ogudu.

“Diesel prices, staff salaries, printing materials, even chalk — everything we need to operate has doubled. If we don’t adjust, we’ll close down.”

Middle-Income Families on the Brink

For families earning between ₦150,000 and ₦300,000 per month, the back-to-school season has become an emotional and financial ordeal.

“We had to remove our last-born from her Montessori school,” says Uche Nnamdi, a bank worker in Port Harcourt.

“Now she’s staying home for a term while we sort out our rent. It’s painful, but it’s the reality.”

Others are turning to installment payments, co-operative societies, or even soft loans from fintech apps to cover the cost of school resumption.

But these short-term fixes often come at a steep cost. According to data from a leading microfinance provider, requests for education-related loans surged by 42% in July alone.

Public Schools, Crowded and Underfunded

With many unable to keep up with private school costs, public schools are now seeing increased enrollments. Unfortunately, this shift brings new challenges.

“Our JSS1 class had 75 students last year. This September, we’re expecting over 100,” says Mrs. Folashade Adeyemi, a teacher at a public secondary school in Alimosho, Lagos.

“We don’t have enough desks, textbooks, or even chalk. The system is overwhelmed.”

While public education remains free in theory, parents still cover “hidden” fees — such as PTA dues, uniforms, and levies for exams or extracurriculars — which add to their burden.

A Call for Intervention

Many are now calling on both federal and state governments to intervene with targeted subsidies or palliatives for education — especially as inflation continues to batter households.

“Education is not a luxury. It is a right,” says Amaka Eze, a child rights advocate.

“If we want to build a competitive and stable Nigeria, we must protect access to quality education — especially for children from working-class families.”

With less than two weeks before most schools resume, the question remains: how many Nigerian parents will be able to afford to send their children back — and how many children will be left behind?